|

|

|

As the procession of years which make up thisthe most wonderful age in human historyadvances in its solemn march, each observer naturally takes a special interest in the question, "What constitutes or wherein consists the superiority of our age above all others?" The answers are as diversified as the minds that look at the subject. The statesman sees it in political forces, the merchant in finances, the mechanic in inventions, the litterateur in education, the husbandman points to the ground, and the laborer holds out his strong arm. But the Christian—and that signifies a fair proportion in every class—will forever give most of the credit to religion as a factor in the progress of the world. Religion, which values time chiefly in its bearing on Eternity, which refers all civilization to the immortal character of the individual, which works in the domain of mind, not matter, which guides the heart before the band of man; religion, whose chart and compass and guiding star is the Golden Rule, "Do unto others whatsoever you would have others do unto you;" religion is not only the counterpart, it is the source and center and motive power of all progressive civilization. Without religion society should inevitably sink back in its physical, productive and progressive capabilities to the condition of the aborigines, where the hand of might was ever uplifted against the weak in open warfare, and one generation took a pride in tearing down as much as the preceding generation had built up.

Religion, or the relation of the creature to the Creator, is not a new thing. It is as old as Adam in some form or other. A great Englishman says, "Man is naturally a religious animal." Again our race has been called "incorrigibly religious."

There is too in western civilization an organized religion-the religion of Jesus Christ. It also is believed to have in it the seeds of immortality. In what consists its vitality that it should not die forever? Is it that it is a "feeling," a little personal keepsake, to be used privately within the darkness of one's domicile and aired on the Sabbath in "pious platitudes" and "glittering generalities?" Or is it rather a power to rouse and raise up and drive men out to do something to dare and do and die—good on the Sabbath and just as good and necessary every other day of the week? What other religion is worth while? What else is the conception of the religion of the Baptist, who hurled defiance at a king on his throne, though he well knew that his head should pay the forfeit? What else the religion of Jesus who "taught as one having authority and not as the scribes," though he foresaw that his words should be sealed by the blood of the gibbet? Religion in this sense means much. It is not sustained by sweet "uplifting" talks which never reach the springs of action. It implies an authoritative power which brooks no other alternative than "thou shalt," and "thou shalt not." Religion, or the relation of the creature to the Creator, is not a new thing. It is as old as Adam in some form or other. A great Englishman says, "Man is naturally a religious animal." Again our race has been called "incorrigibly religious."

There is too in western civilization an organized religion-the religion of Jesus Christ. It also is believed to have in it the seeds of immortality. In what consists its vitality that it should not die forever? Is it that it is a "feeling," a little personal keepsake, to be used privately within the darkness of one's domicile and aired on the Sabbath in "pious platitudes" and "glittering generalities?" Or is it rather a power to rouse and raise up and drive men out to do something to dare and do and die—good on the Sabbath and just as good and necessary every other day of the week? What other religion is worth while? What else is the conception of the religion of the Baptist, who hurled defiance at a king on his throne, though he well knew that his head should pay the forfeit? What else the religion of Jesus who "taught as one having authority and not as the scribes," though he foresaw that his words should be sealed by the blood of the gibbet? Religion in this sense means much. It is not sustained by sweet "uplifting" talks which never reach the springs of action. It implies an authoritative power which brooks no other alternative than "thou shalt," and "thou shalt not."

Now if these things be true; if religion was implanted originally in the heart of mankind, if its meaning was taught and exemplified by Jesus in the flesh and his Baptist herald, if it is immortalized for the safeguarding and success and salvation of society, the inference is no less certain that there is no conceivable possibility of preserving, propagating and perpetuating religion except by the authorized teaching of the Christian church. America, like other nations, is inherently religious and American intelligence approves of Christianity, but our present people refuse to attach much importance to the church andstrange to findthe more learning Professor Ethics and Dr. Supernatural pretend to possess, the less seriously they are taken. Consistency, if not gratitude for freedom, should compel us to be Christians. We are a nation of equals who are brothersbrothers of Jesus Christone as nearly related as the other. The Redeemer is both our preceptor and pattern. He "hath put down the mighty and exalted the lowly." He declared of himself that he "came to minister, not to be ministered to." In America all are servants—the president is a servant, merchants are servants to their customers, doctors to their patients and the clergy to their parishioners. Americans, too, are all workers. Among them work is honorable—the useful is always noble. God grant that it may remain so. When we get to despise work we are going a long way back to the eighteenth century—back to pre-Christian paganism. Now if these things be true; if religion was implanted originally in the heart of mankind, if its meaning was taught and exemplified by Jesus in the flesh and his Baptist herald, if it is immortalized for the safeguarding and success and salvation of society, the inference is no less certain that there is no conceivable possibility of preserving, propagating and perpetuating religion except by the authorized teaching of the Christian church. America, like other nations, is inherently religious and American intelligence approves of Christianity, but our present people refuse to attach much importance to the church andstrange to findthe more learning Professor Ethics and Dr. Supernatural pretend to possess, the less seriously they are taken. Consistency, if not gratitude for freedom, should compel us to be Christians. We are a nation of equals who are brothersbrothers of Jesus Christone as nearly related as the other. The Redeemer is both our preceptor and pattern. He "hath put down the mighty and exalted the lowly." He declared of himself that he "came to minister, not to be ministered to." In America all are servants—the president is a servant, merchants are servants to their customers, doctors to their patients and the clergy to their parishioners. Americans, too, are all workers. Among them work is honorable—the useful is always noble. God grant that it may remain so. When we get to despise work we are going a long way back to the eighteenth century—back to pre-Christian paganism.

History, profane, sacred and ecclesiastical, is said to be the recorded lives of a few individualskings, heroes, authors, inventors, saintstheir names in life are on every tongue and after death they go ringing down the corridors of time. But in a democracy where all are servants are not all kings, too? In a sense every man is a herothe hero of his own destiny. There is no man born into this world without a destiny—he is sent here for a special end and purpose. If he is true to his colors, faithful to his Creator, strong in the pursuit of his life purpose, he is verily a hero. His name may not shine of "Fame's eternal bederoll worthy to be filed," still though hidden here in the ranks of the unknown he has his angelic Plutarch who will make full record of his deeds in the "Book of Life," and beyond the stars his name and fame will reverberate down through the ages of eternity. The statesman and the soldier may hold up their hands and swear allegiance to the flag, that is to say they are willing to shed their heart's blood for it—a noble thought—it swells every heart that walks to war, but there is a loyalty higher than obedience to purpled royalty or popular congress, it is fidelity to the flag of the Crossa holocaust of service to follow in the footsteps of a crucified King and, like Peter, the Hermit, induce others to enter the ranks "God wills it" "Onward Christian soldiers, marching as to war." History, profane, sacred and ecclesiastical, is said to be the recorded lives of a few individualskings, heroes, authors, inventors, saintstheir names in life are on every tongue and after death they go ringing down the corridors of time. But in a democracy where all are servants are not all kings, too? In a sense every man is a herothe hero of his own destiny. There is no man born into this world without a destiny—he is sent here for a special end and purpose. If he is true to his colors, faithful to his Creator, strong in the pursuit of his life purpose, he is verily a hero. His name may not shine of "Fame's eternal bederoll worthy to be filed," still though hidden here in the ranks of the unknown he has his angelic Plutarch who will make full record of his deeds in the "Book of Life," and beyond the stars his name and fame will reverberate down through the ages of eternity. The statesman and the soldier may hold up their hands and swear allegiance to the flag, that is to say they are willing to shed their heart's blood for it—a noble thought—it swells every heart that walks to war, but there is a loyalty higher than obedience to purpled royalty or popular congress, it is fidelity to the flag of the Crossa holocaust of service to follow in the footsteps of a crucified King and, like Peter, the Hermit, induce others to enter the ranks "God wills it" "Onward Christian soldiers, marching as to war."

The call of the modern crusader of Christ to come, take possession of the "kingdom prepared from the foundation of the world," seems to fall on deaf ears. People have reversed the order of seeking (secondly) "the kingdom of God and his righteousness," and have transferred their dependence from religious to secular societies. Indeed it takes a great deal of courage to be a preacher nowadays, when what was once regarded as "beatitudes" are looked upon as simple platitudes, when the hearers are so saturated with worldliness that not only the manner of delivering the message is criticized, but the matter of the message is questioned and doubts raised as to whether it came from God, and when, moreover, the only weapon the speaker can appeal to—the power of an unanimous church—lies broken into two hundred and fifty fragments in his hands. Well, how much is the church herself to blame for this powerlessness? Has not the human mixed with the divine—weeds with roses? It is a poor sort of piety to kneel down and pray the prayer of the Prince of Peace"Love one another as I have loved you," and then to stand up and preach the practice described in Butler's Hudibras, of "hating each other for the love of God." The old axiom will forever hold true, "United we stand, divided we fall." The only Archimedean lever to lift the world is the unadulterated Word, spoken first by the Man of Galilee and repeated by the undying voice of an united church. The church is the agent commissioned by the Savior to "teach all nations," and the preacher speaks not in his own name but in the name of a divinely established church. The call of the modern crusader of Christ to come, take possession of the "kingdom prepared from the foundation of the world," seems to fall on deaf ears. People have reversed the order of seeking (secondly) "the kingdom of God and his righteousness," and have transferred their dependence from religious to secular societies. Indeed it takes a great deal of courage to be a preacher nowadays, when what was once regarded as "beatitudes" are looked upon as simple platitudes, when the hearers are so saturated with worldliness that not only the manner of delivering the message is criticized, but the matter of the message is questioned and doubts raised as to whether it came from God, and when, moreover, the only weapon the speaker can appeal to—the power of an unanimous church—lies broken into two hundred and fifty fragments in his hands. Well, how much is the church herself to blame for this powerlessness? Has not the human mixed with the divine—weeds with roses? It is a poor sort of piety to kneel down and pray the prayer of the Prince of Peace"Love one another as I have loved you," and then to stand up and preach the practice described in Butler's Hudibras, of "hating each other for the love of God." The old axiom will forever hold true, "United we stand, divided we fall." The only Archimedean lever to lift the world is the unadulterated Word, spoken first by the Man of Galilee and repeated by the undying voice of an united church. The church is the agent commissioned by the Savior to "teach all nations," and the preacher speaks not in his own name but in the name of a divinely established church.

A great American once asserted that he acknowledged no leading light except the lamp of experience. He meant, no doubt, the experience of his own country; he thought nothing of the rest of the world. After its independence America is even more unwilling to learn in any other school than that of actual experience. But later or sooner the day will dawn—good for church and state—when the American people will be convinced by experience that "man does not live on bread alone," neither do churches live on mutual contradictions alone. Oh, for the time when all God's children will be one, as God is one, in the faith of St. Augustine—"non essentials, liberty—essentials, unity—all things, charity." The prayer of Moses comes to mind, "Oh, that they were wise and would understand." It was his last word for his chosen people. A great American once asserted that he acknowledged no leading light except the lamp of experience. He meant, no doubt, the experience of his own country; he thought nothing of the rest of the world. After its independence America is even more unwilling to learn in any other school than that of actual experience. But later or sooner the day will dawn—good for church and state—when the American people will be convinced by experience that "man does not live on bread alone," neither do churches live on mutual contradictions alone. Oh, for the time when all God's children will be one, as God is one, in the faith of St. Augustine—"non essentials, liberty—essentials, unity—all things, charity." The prayer of Moses comes to mind, "Oh, that they were wise and would understand." It was his last word for his chosen people.

Many elements make for success in the ministry of the church. First, genius is not a necessity. Alexander Hamilton was a genius. He created the United States treasury. He could not keep his own accounts. Napoleon was a matchless genius. He could conquer nations. He could not drill a single regiment in the manual of arms. A minister needs talent, though not extraordinary brain brilliancy. The secret of success is difficult to detect and is not the same in all. There is a talent of the heart, often more potent than power of mind. But an indispensable requisite is what is called the "personal equation," that is, broadly speaking, a certain something in the man. Is it magnetism, is it born, or is it acquireda faculty of managing other men-a gift of effectiveness possessed by not one person in five hundred? Many elements make for success in the ministry of the church. First, genius is not a necessity. Alexander Hamilton was a genius. He created the United States treasury. He could not keep his own accounts. Napoleon was a matchless genius. He could conquer nations. He could not drill a single regiment in the manual of arms. A minister needs talent, though not extraordinary brain brilliancy. The secret of success is difficult to detect and is not the same in all. There is a talent of the heart, often more potent than power of mind. But an indispensable requisite is what is called the "personal equation," that is, broadly speaking, a certain something in the man. Is it magnetism, is it born, or is it acquireda faculty of managing other men-a gift of effectiveness possessed by not one person in five hundred?

A churchman's standing in his community is not altogether owing to personal merit. It is official. He is a representative of a great servicethe ministry of the churchthe greatest service that ever was or will be instituted on this earth. Any recognition accorded him is a tribute to the ministry of the church. It is furthermore, perhaps, an implied estimate not of what he is, but of what he ought to be a man of God. A churchman's standing in his community is not altogether owing to personal merit. It is official. He is a representative of a great servicethe ministry of the churchthe greatest service that ever was or will be instituted on this earth. Any recognition accorded him is a tribute to the ministry of the church. It is furthermore, perhaps, an implied estimate not of what he is, but of what he ought to be a man of God.

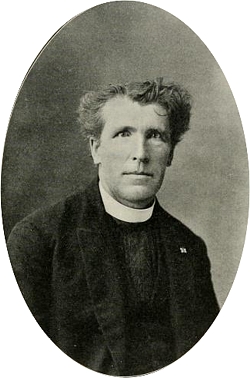

Jones county has a minister endowed with some of the attributes, positive and negative, that contribute to the good of Christianity and the growth of the church. He has helped, more than a little, to raise the standard of the Cross, break down the walls of prejudice, bring all men to see one another over denominational picket-fences, and make the church pastor respected in the ranks of the community. This is the Rev. Robert Powers, rector of St. Patrick's church, Anamosa. He is the oldest minister in the county, both in point of years and service. He has done parochial duty in two churches for twenty-eight years. He has baptized and shrived and married and buried almost a generation of people. He has walked daily before the populace, rejoiced in their rejoicing, borne a part of their weight of woe, and tried to help others to bear their burden. In season and out of season, in every work-mental, manual, social and spiritual, he has taken a man's part. Jones county has a minister endowed with some of the attributes, positive and negative, that contribute to the good of Christianity and the growth of the church. He has helped, more than a little, to raise the standard of the Cross, break down the walls of prejudice, bring all men to see one another over denominational picket-fences, and make the church pastor respected in the ranks of the community. This is the Rev. Robert Powers, rector of St. Patrick's church, Anamosa. He is the oldest minister in the county, both in point of years and service. He has done parochial duty in two churches for twenty-eight years. He has baptized and shrived and married and buried almost a generation of people. He has walked daily before the populace, rejoiced in their rejoicing, borne a part of their weight of woe, and tried to help others to bear their burden. In season and out of season, in every work-mental, manual, social and spiritual, he has taken a man's part.

Of his childhood little is known. His experiences were probably the same as were common to other children brought up in the same country, marked possibly by the prophecies of partial friends as to his future. Neither was his mature life distinguished by any glamour of circumstance. Born on the 18th of August, 1851, in Kilkenny county, Ireland, he saw the sun set behind the hill of Slievenamon every evening for more than a score of his youthful years. Attending the common schools of the locality, gifted with a good memory and mental vigor, he utilized the advantages received in preparation for the work which be believed he might some day be able to accomplish. A "divine vocation" as it is termed, is one of the secrets hidden in the heart of the Eternal. "There is a divinity that shapes our ends." To what extent that divinity is controllable by our own selves, there are numerous reminders in the lives of men. Possibly nature and grace and Providential and parental care combine to carry out the decree of Omnipotence. "The Spirit breatheth where he will." Nature alone can do nothing more than employ its native ability, in obedience to reason, and reason itself in obedience to the mandates of Mount Sinai-unto the end which will have solved the great mystery. Of his childhood little is known. His experiences were probably the same as were common to other children brought up in the same country, marked possibly by the prophecies of partial friends as to his future. Neither was his mature life distinguished by any glamour of circumstance. Born on the 18th of August, 1851, in Kilkenny county, Ireland, he saw the sun set behind the hill of Slievenamon every evening for more than a score of his youthful years. Attending the common schools of the locality, gifted with a good memory and mental vigor, he utilized the advantages received in preparation for the work which be believed he might some day be able to accomplish. A "divine vocation" as it is termed, is one of the secrets hidden in the heart of the Eternal. "There is a divinity that shapes our ends." To what extent that divinity is controllable by our own selves, there are numerous reminders in the lives of men. Possibly nature and grace and Providential and parental care combine to carry out the decree of Omnipotence. "The Spirit breatheth where he will." Nature alone can do nothing more than employ its native ability, in obedience to reason, and reason itself in obedience to the mandates of Mount Sinai-unto the end which will have solved the great mystery.

In his seventeenth year, with an ordinary share of school learning, with general impressions of the world of the present and of the future, the subject of this sketch entered a classical school conducted by the Carmelites. From the beginning he showed little taste for muscular amusements but devoted himself to books with a singular determination and ambition. In his seventeenth year, with an ordinary share of school learning, with general impressions of the world of the present and of the future, the subject of this sketch entered a classical school conducted by the Carmelites. From the beginning he showed little taste for muscular amusements but devoted himself to books with a singular determination and ambition.

In 1871 he went to a college (seminary) in charge of the Trappist monks, at Mount Melleray, the parent house of the monastery of that name in Dubuque county. The lives of the recluses residing in that retreat, admirable if not enviable as they are, make an impression which can never be effaced from the memory of any one who witnesses their modus vivendi, even from a distance. There, more than in any other spot at this side of heaven, will a youthful secular see illustrated the object lesson, "what profiteth it a man to gain the whole world?" In 1871 he went to a college (seminary) in charge of the Trappist monks, at Mount Melleray, the parent house of the monastery of that name in Dubuque county. The lives of the recluses residing in that retreat, admirable if not enviable as they are, make an impression which can never be effaced from the memory of any one who witnesses their modus vivendi, even from a distance. There, more than in any other spot at this side of heaven, will a youthful secular see illustrated the object lesson, "what profiteth it a man to gain the whole world?"

After spending two years at that abode of solitude, sanctity and scholarship in the study of the "humanities" and mental philosophy, our graduate took his place in the theological seminary at Callow for a four years' course in physics and divinity. After spending two years at that abode of solitude, sanctity and scholarship in the study of the "humanities" and mental philosophy, our graduate took his place in the theological seminary at Callow for a four years' course in physics and divinity.

May 26, 1877, he was promoted to Holy Orders for the diocese of Dubuque, Iowa. The usual period of vacation, given in order to rest, recruit, and enjoy the associations of relatives and friends before the final farewell, was cut short in this case by a dispatch to appear at the opening of the scholastic year in September to serve as teacher in St. Joseph's College, Dubuque. May 26, 1877, he was promoted to Holy Orders for the diocese of Dubuque, Iowa. The usual period of vacation, given in order to rest, recruit, and enjoy the associations of relatives and friends before the final farewell, was cut short in this case by a dispatch to appear at the opening of the scholastic year in September to serve as teacher in St. Joseph's College, Dubuque.

In August, 1877, looking his last on the scenes of home and childhood and friends and country, he crossed the Atlantic, with the greater part of the continent, and on the morning after arrival on the west banks of the Mississippi he began his life work of teacher and preacher and pastor, which has continued without interruption up to the present and is likely to continue, without change of operations or scenery, until the Fates call on him to "shake off the mortal coil." In August, 1877, looking his last on the scenes of home and childhood and friends and country, he crossed the Atlantic, with the greater part of the continent, and on the morning after arrival on the west banks of the Mississippi he began his life work of teacher and preacher and pastor, which has continued without interruption up to the present and is likely to continue, without change of operations or scenery, until the Fates call on him to "shake off the mortal coil."

After six years spent alternating between parochial work at the cathedral and teaching at the college, sometimes combining both, half the day at one place and half at the other, he came to reside in Jones county in October, 1882. Here his face has been to the grindstone of pastoral duty, with only a single month's intermission, for nearly three decades. No hope of revisiting old scenes except in dreams no hope of earthly reward except a sufficiency of food and clothing, that is all the world can give anyway and that is all it is asked to give. It is surely a relief to be one's own executor in every sense of the word, financially, socially and spiritually. Like Longfellow's Village Blacksmith, "he can look the whole world in the face." Like him who had not "whereon to lay his head" it is abundant compensation to be able to sit down and rest on the accumulations of a third of a century of toil, to challenge the multitude, "which of you will accuse me of eating the bread of idleness?" As Abraham Lincoln well said, "With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us finish the work we are in." The Nestor of the clergy in Jones county is satisfied. He has no further ambition or desire than to be able, whilst yet he "encumbereth the ground," to administer to the people that a merciful God has committed to his charge, to be laid out in final farewell before the white altar of St. Patrick's church and to rest in the shadow of its steeple until the Archangel's trumpet will call him to come at the head of his parishioners into the Valley of judgment. After six years spent alternating between parochial work at the cathedral and teaching at the college, sometimes combining both, half the day at one place and half at the other, he came to reside in Jones county in October, 1882. Here his face has been to the grindstone of pastoral duty, with only a single month's intermission, for nearly three decades. No hope of revisiting old scenes except in dreams no hope of earthly reward except a sufficiency of food and clothing, that is all the world can give anyway and that is all it is asked to give. It is surely a relief to be one's own executor in every sense of the word, financially, socially and spiritually. Like Longfellow's Village Blacksmith, "he can look the whole world in the face." Like him who had not "whereon to lay his head" it is abundant compensation to be able to sit down and rest on the accumulations of a third of a century of toil, to challenge the multitude, "which of you will accuse me of eating the bread of idleness?" As Abraham Lincoln well said, "With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us finish the work we are in." The Nestor of the clergy in Jones county is satisfied. He has no further ambition or desire than to be able, whilst yet he "encumbereth the ground," to administer to the people that a merciful God has committed to his charge, to be laid out in final farewell before the white altar of St. Patrick's church and to rest in the shadow of its steeple until the Archangel's trumpet will call him to come at the head of his parishioners into the Valley of judgment.

Source: History of Jones County, Iowa, Past and Present, R. M. Corbitt, S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., Chicago, 1910, p. 400.

|

|

|