Story and photos provided by Phillip Ralph Owen.

|

You can watch a brief recent video of Clay Mills on You Tube. |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

by Phillip Ralph Owen

During the last few years of his life, my father compiled a "first edition" of his stories and poems. This "second edition" is dedicated with a wish that children everywhere may have their own special memories. During the last few years of his life, my father compiled a "first edition" of his stories and poems. This "second edition" is dedicated with a wish that children everywhere may have their own special memories.

Dad's stories and poems recall vivid memories of his childhood during the years just after the First World War. His stories give a small glimpse of events that shaped and gave meaning to his life, as he recalls memories of a moment for which we all share a common bond, our own childhood. Dad's stories and poems recall vivid memories of his childhood during the years just after the First World War. His stories give a small glimpse of events that shaped and gave meaning to his life, as he recalls memories of a moment for which we all share a common bond, our own childhood.

Dad's father, Hiland Charles Owen, born 1876, was the fifth child, in a family of two brothers and three sisters. We believe that Hiley Owen's ancestors arrived in America sometime in the 1700s, then moved to Canada before coming to Iowa in the mid–1800's. I've not heard much history about Grandpa Hiley, except that he liked to play baseball. Grandpa Hiley liked to play the fiddle and often rode horseback for several miles to entertain at nearby house dances. During the long winter months, Dad and his older brother, Harold, helped Grandpa make several fiddles. He must have had an ear for music because he also tuned pianos. Dad's father, Hiland Charles Owen, born 1876, was the fifth child, in a family of two brothers and three sisters. We believe that Hiley Owen's ancestors arrived in America sometime in the 1700s, then moved to Canada before coming to Iowa in the mid–1800's. I've not heard much history about Grandpa Hiley, except that he liked to play baseball. Grandpa Hiley liked to play the fiddle and often rode horseback for several miles to entertain at nearby house dances. During the long winter months, Dad and his older brother, Harold, helped Grandpa make several fiddles. He must have had an ear for music because he also tuned pianos.

Grandpa Hiley's brother, Thomas, had moved to Illinois to work in the coal mines. Grandpa Hiley's sister, Aunt Ida, had married and moved to Oklahoma. Even though separated by a great distance, I remember Dad and my aunts and uncles would speak of visits from Uncle Percy and Aunt Ida driving from Oklahoma and Uncle Tom and Aunt Edna visiting from Illinois. Grandpa Hiley's brother, Thomas, had moved to Illinois to work in the coal mines. Grandpa Hiley's sister, Aunt Ida, had married and moved to Oklahoma. Even though separated by a great distance, I remember Dad and my aunts and uncles would speak of visits from Uncle Percy and Aunt Ida driving from Oklahoma and Uncle Tom and Aunt Edna visiting from Illinois.

Dad's mother, Helena Margaret Schneckloth, born 1882, in Germany, came to America with her parents when she was about one year old. I still remember that we stored her family's steamer trunk at the Caves Farm until it fell apart from dry rot. I have many fond memories of Grandma Helena. She had only one brother, Willam, who never married. With only one brother, Grandma Helena must have been a little overwhelmed with Grandpa's large family—and then raising seven children of her own. I remember her as a quiet and patient lady, with few complaints. After Grandpa Hiley died, Grandma moved out of her small home at the south edge of Maquoketa. For last years of her life, she lived with each of her children for several months at a time. Dad's mother, Helena Margaret Schneckloth, born 1882, in Germany, came to America with her parents when she was about one year old. I still remember that we stored her family's steamer trunk at the Caves Farm until it fell apart from dry rot. I have many fond memories of Grandma Helena. She had only one brother, Willam, who never married. With only one brother, Grandma Helena must have been a little overwhelmed with Grandpa's large family—and then raising seven children of her own. I remember her as a quiet and patient lady, with few complaints. After Grandpa Hiley died, Grandma moved out of her small home at the south edge of Maquoketa. For last years of her life, she lived with each of her children for several months at a time.

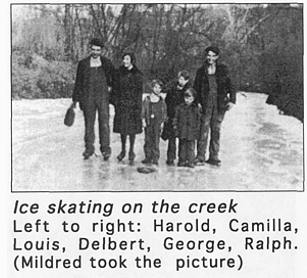

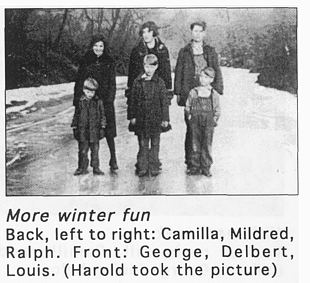

I don't know the details of how Hiland Owen met or courted Helena Schneckloth. History records that they were married in 1908. They raised seven children to adulthood— I don't know the details of how Hiland Owen met or courted Helena Schneckloth. History records that they were married in 1908. They raised seven children to adulthood—

| Harold | Jan. 24, 1909 |  |

| | Mildred | July 25, 1912 | |

| | Ralph | July 11, 1914 | |

| | Camilla | Dec. 23, 1915 | |

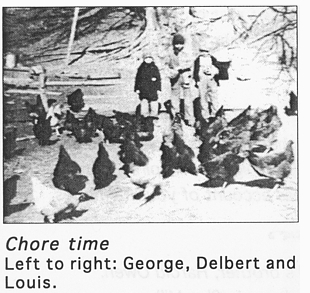

| | Delbert | Sept. 2, 1918 | |

| | Louis | Oct. 19, 1921 | |

| | George | Sept. 28, 1923 | |

| | (There were also two boys who died shortly after birth or were stillborn.) |

My Dad, Ralph, was born on a farm near Delmar Iowa, where Grandpa Hiley and his brother Lemuel were farming. About the year Dad was born, the farming operation had some serious financial losses. The family began an almost yearly process of moving from farm to farm in Clinton and Jackson and Jones County. My Dad, Ralph, was born on a farm near Delmar Iowa, where Grandpa Hiley and his brother Lemuel were farming. About the year Dad was born, the farming operation had some serious financial losses. The family began an almost yearly process of moving from farm to farm in Clinton and Jackson and Jones County.

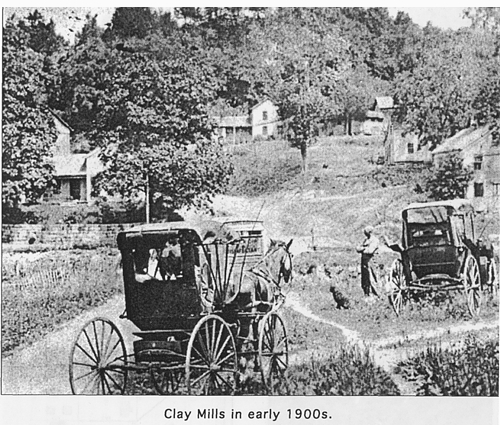

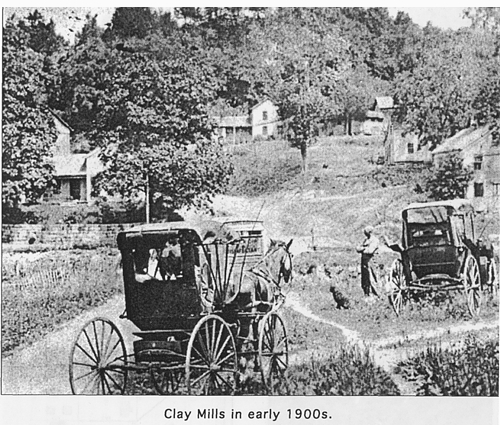

In 1922, the Hiley Owen family decided to move to Clay Mills. It was a very small village, located in the northeast corner of Jones County, and by then already well past any chance of growing in size. It's my best guess that the move to Clay Mills probably held a promise of economic survival for a family of six, and soon to be seven children. Although Dad once said. "The depression came early and stayed late in hills of eastern Iowa," his stories don't speak of hunger or lack of clothes or shelter. And, we know the family survived—probably better than some families. The move to Clay Mills proved to be a most memorable event for my father. It also proved to be a permanent, although isolated, address for nearly eight years—the longest time the Hiley Owen family had lived at the same address. In 1922, the Hiley Owen family decided to move to Clay Mills. It was a very small village, located in the northeast corner of Jones County, and by then already well past any chance of growing in size. It's my best guess that the move to Clay Mills probably held a promise of economic survival for a family of six, and soon to be seven children. Although Dad once said. "The depression came early and stayed late in hills of eastern Iowa," his stories don't speak of hunger or lack of clothes or shelter. And, we know the family survived—probably better than some families. The move to Clay Mills proved to be a most memorable event for my father. It also proved to be a permanent, although isolated, address for nearly eight years—the longest time the Hiley Owen family had lived at the same address.

Dad began his book of poems and stories with following introduction inside the front cover of each one of the four books he and Mom complied and gave to each of the families of their four boys for Christmas, 1986— Dad began his book of poems and stories with following introduction inside the front cover of each one of the four books he and Mom complied and gave to each of the families of their four boys for Christmas, 1986—

Lifetime Stories And Poems

BY RALPH WILLIAM OWEN

I have written a short version of what life was like when I was a boy from seven years old to my early teens. The few short poems I wrote in the past couple of years, as I went for my daily walk, these thoughts came to mind and I wrote them down and thought they might be of some interest to you and your family. I present them to you as token of love and appreciation for all the things you have done for us. You have given us grandchildren that we have enjoyed very much. You have always been thoughtful by remembering our birthdays and anniversaries and helpful in sickness and health. So for all you have done for us, we say a big thank you and wish you and your family many long years of a happy and joyful life. With Love, I have written a short version of what life was like when I was a boy from seven years old to my early teens. The few short poems I wrote in the past couple of years, as I went for my daily walk, these thoughts came to mind and I wrote them down and thought they might be of some interest to you and your family. I present them to you as token of love and appreciation for all the things you have done for us. You have given us grandchildren that we have enjoyed very much. You have always been thoughtful by remembering our birthdays and anniversaries and helpful in sickness and health. So for all you have done for us, we say a big thank you and wish you and your family many long years of a happy and joyful life. With Love,

Mom and Dad Mom and Dad

August 29, 1986 August 29, 1986

"LIVING AT CLAY MILLS IN THE 1920s"

I remember well the spring we moved to Clay Mills. It was late March or early April. I was seven years old. I remember very well of walking along the dirt road a half mile or more east of Clay Mills with my younger sister, driving five or six cows and wondering what it would be like when we got there. There was six of us kids (George was born later at Clay Mills) and I was third from the oldest. So, for my older brother and two sisters it was, an exciting time. As we went down the long hill to where the house and building were, we saw the creek running below the hill and all the big rocks and trees on the hillside and talked about what a nice place to be to just have fun. This was before TV, radio, telephone or even RFD (Rural Free Delivery of mail). We walked about a mile to get any mail. So, what fun we had, we made ourselves, but always found something for excitement. I remember well the spring we moved to Clay Mills. It was late March or early April. I was seven years old. I remember very well of walking along the dirt road a half mile or more east of Clay Mills with my younger sister, driving five or six cows and wondering what it would be like when we got there. There was six of us kids (George was born later at Clay Mills) and I was third from the oldest. So, for my older brother and two sisters it was, an exciting time. As we went down the long hill to where the house and building were, we saw the creek running below the hill and all the big rocks and trees on the hillside and talked about what a nice place to be to just have fun. This was before TV, radio, telephone or even RFD (Rural Free Delivery of mail). We walked about a mile to get any mail. So, what fun we had, we made ourselves, but always found something for excitement.

We moved to Clay Mills in 1922 and lived there until 1930. The farm, was owned by the John Sagers family and we agreed to pay so much rent—I don't remember how much—but the agreement was that we could clear brush and trees from the land at so much an acre—again how much, I don't remember. But we were glad to do it because times were tough and income was low from milking a few cows and raising few pigs. But the Sagers were always good to us and helped us in many ways. I remember Fay and Paul Sagers used to come up two or three times a year to go hunting or look for Indian Artifacts and even if we were doing some special job our Dad usually let us take time off to go with them and we always had fun. We moved to Clay Mills in 1922 and lived there until 1930. The farm, was owned by the John Sagers family and we agreed to pay so much rent—I don't remember how much—but the agreement was that we could clear brush and trees from the land at so much an acre—again how much, I don't remember. But we were glad to do it because times were tough and income was low from milking a few cows and raising few pigs. But the Sagers were always good to us and helped us in many ways. I remember Fay and Paul Sagers used to come up two or three times a year to go hunting or look for Indian Artifacts and even if we were doing some special job our Dad usually let us take time off to go with them and we always had fun.

Our life was unhurried and slow paced. Each day was lived like the day before—no big decision to make—like buying a new car or tractor or anything else, for we bought very little except for few basic food items like flour, sugar and other things that could not be grown. We had no bills, like heat, water, telephone, electricity or liability insurance or car insurance or health insurance. These were all things which I had never heard about. Any changes were routine—like the weather and the seasons. While work changed according to the time of the year, it was much the same year after year. Our life was unhurried and slow paced. Each day was lived like the day before—no big decision to make—like buying a new car or tractor or anything else, for we bought very little except for few basic food items like flour, sugar and other things that could not be grown. We had no bills, like heat, water, telephone, electricity or liability insurance or car insurance or health insurance. These were all things which I had never heard about. Any changes were routine—like the weather and the seasons. While work changed according to the time of the year, it was much the same year after year.

In the spring even before the all the snow had melted and the ground was dry, we got ready for spring planting. First we cleared the land and hauled the stump that had been pulled the fall before. Sometimes it would be only an acre or two each year. But once, I remember we cleared about ten acres, and that was quite a job to plow the first time. There were many roots left from grubbing the trees and it was slow and tedious work to plow. We had three horses on a special breaking plow with a very big wooden beam. It was my job to stand on that beam while my older brothers or dad held on to the plow handles. If we hit some big roots the plow stopped for the horses could not pull it. Then we had to chop down the side of the plow with an ax and cut the root. The horses walked real slow knowing it could happen anytime and was quite a jolt on their shoulders. I don't remember how long it took to plow but as I recall we never done more than a half acre a day and some days not that much. In the spring even before the all the snow had melted and the ground was dry, we got ready for spring planting. First we cleared the land and hauled the stump that had been pulled the fall before. Sometimes it would be only an acre or two each year. But once, I remember we cleared about ten acres, and that was quite a job to plow the first time. There were many roots left from grubbing the trees and it was slow and tedious work to plow. We had three horses on a special breaking plow with a very big wooden beam. It was my job to stand on that beam while my older brothers or dad held on to the plow handles. If we hit some big roots the plow stopped for the horses could not pull it. Then we had to chop down the side of the plow with an ax and cut the root. The horses walked real slow knowing it could happen anytime and was quite a jolt on their shoulders. I don't remember how long it took to plow but as I recall we never done more than a half acre a day and some days not that much.

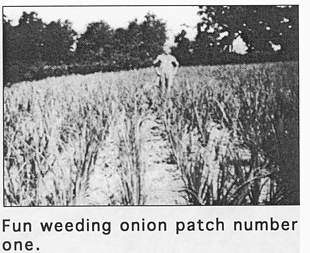

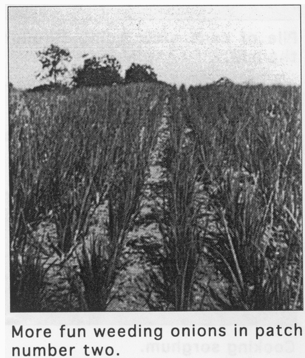

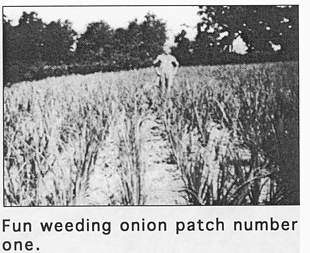

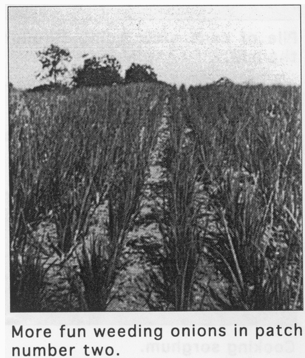

After the new ground was plowed we began to plow the other small plot for corn—maybe ten to fifteen acres and several small plots for garden crops of all kinds. We always planted a lot of ordinary things like tomatoes, two or three kinds of beans and maybe a half-acre or more of navy beans. We always had at least one or two acres of onions and three or four acres of cane sorghum. We always had lots of potatoes to last the year around. I think we had about a hundred-fifty bushels of onions and about two hundred gallons of sorghum. We sold the onions wholesale to the stores in town for one dollar a bushel and most of the molasses for a dollar a gallon. The first two or three years we had less sorghum and onions but it was all planted by hand. There were always four or five us at work but it took a long time. May was a busy month as everything had to be planted from about the tenth to last of the month. After the new ground was plowed we began to plow the other small plot for corn—maybe ten to fifteen acres and several small plots for garden crops of all kinds. We always planted a lot of ordinary things like tomatoes, two or three kinds of beans and maybe a half-acre or more of navy beans. We always had at least one or two acres of onions and three or four acres of cane sorghum. We always had lots of potatoes to last the year around. I think we had about a hundred-fifty bushels of onions and about two hundred gallons of sorghum. We sold the onions wholesale to the stores in town for one dollar a bushel and most of the molasses for a dollar a gallon. The first two or three years we had less sorghum and onions but it was all planted by hand. There were always four or five us at work but it took a long time. May was a busy month as everything had to be planted from about the tenth to last of the month.

The next big job was weeding onions. The rows were about fifteen inches apart. The seedlings as they came up were very small and grew slow so every row had to be weeded by hand. It was slow and hard, tedious work but we done it because we had to earn some cash any way we could. There was no minimum wage or no part-time jobs to be had. Day after day it was the same job. Every morning my dad would say "Come on kids lets go up to the hill to the onion patch." It was always up the hill because there was no other way, and we always went without complaining. Many years later my younger sister asked me, "How come when Dad said come on let's go up to the onion patch—we always went without complaining?" I said, "Well there was no other place or way to go anywhere else and we wanted to go somewhere, so we up the hill we went." The next big job was weeding onions. The rows were about fifteen inches apart. The seedlings as they came up were very small and grew slow so every row had to be weeded by hand. It was slow and hard, tedious work but we done it because we had to earn some cash any way we could. There was no minimum wage or no part-time jobs to be had. Day after day it was the same job. Every morning my dad would say "Come on kids lets go up to the hill to the onion patch." It was always up the hill because there was no other way, and we always went without complaining. Many years later my younger sister asked me, "How come when Dad said come on let's go up to the onion patch—we always went without complaining?" I said, "Well there was no other place or way to go anywhere else and we wanted to go somewhere, so we up the hill we went."

There was a lot of hoeing to do in the cane field but it was planted in rows like corn and cultivated with horses so that helped a lot—saved a lot of hoeing. I remember one year we had about ten acres of field corn on new ground and the roots left from grubbing were so bad we couldn't cultivate it so we hoed the whole field by hand. Even with five of us it took a long time but we got done and had fairly good corn. From mid-July to the last of August was a slack time. A time us kids looked forward to because we had more time ourselves to roam the hills and wade in the creek. Sometimes in dry years, we had a to herd cows in the unfenced timber. But that was not so bad—except boring at times. We usually had some fun some way. We rode the old plow horses and they couldn't go very fast but we had to race a little. We had to stay on the horses because of rattlesnakes. One time I remember one rattled very near the horse and I was afraid the horse would panic and throw me off but they didn't seem much afraid. There was a lot of hoeing to do in the cane field but it was planted in rows like corn and cultivated with horses so that helped a lot—saved a lot of hoeing. I remember one year we had about ten acres of field corn on new ground and the roots left from grubbing were so bad we couldn't cultivate it so we hoed the whole field by hand. Even with five of us it took a long time but we got done and had fairly good corn. From mid-July to the last of August was a slack time. A time us kids looked forward to because we had more time ourselves to roam the hills and wade in the creek. Sometimes in dry years, we had a to herd cows in the unfenced timber. But that was not so bad—except boring at times. We usually had some fun some way. We rode the old plow horses and they couldn't go very fast but we had to race a little. We had to stay on the horses because of rattlesnakes. One time I remember one rattled very near the horse and I was afraid the horse would panic and throw me off but they didn't seem much afraid.

About the first of September it was time to pull the onions. They were all pulled from the ground and tops removed and stored in a dry place so they would dry more before ready for sale. We usually stored them with tops on in the old house and then on rainy days we would top onions all day. For a boy my age it was monotonous work and there were days I dreamed of growing up and being rich—like being a banker or some other job where I had lots of money. But we also had lots of fun telling stories or talking about inventing a machine that would pick and top onions without ever having to touch them. I'm sure they have such a machine today but the bank may very well own it and probably be worn out before it is paid for. But I doubt if when they got done they have the same feeling of pride and satisfaction of having done a job that had to be done by hand and no other way to do it—a feeling of being independent and self-supporting and not having to worry about buying a machine and wondering if it would be paid for before it wore out. About the first of September it was time to pull the onions. They were all pulled from the ground and tops removed and stored in a dry place so they would dry more before ready for sale. We usually stored them with tops on in the old house and then on rainy days we would top onions all day. For a boy my age it was monotonous work and there were days I dreamed of growing up and being rich—like being a banker or some other job where I had lots of money. But we also had lots of fun telling stories or talking about inventing a machine that would pick and top onions without ever having to touch them. I'm sure they have such a machine today but the bank may very well own it and probably be worn out before it is paid for. But I doubt if when they got done they have the same feeling of pride and satisfaction of having done a job that had to be done by hand and no other way to do it—a feeling of being independent and self-supporting and not having to worry about buying a machine and wondering if it would be paid for before it wore out.

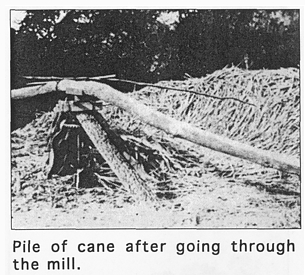

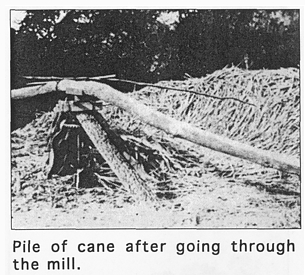

As soon as the onions were harvested and stored it was time make sorghum. First we had to strip all the leaves off the cane while still standing in the field. We did this by making sort of a wooden sword with a good handle but not very sharp otherwise it would damage the stalk. Just start at the stalk and strike down right next to the stalk and about two or three swipes and you had the leaves. But three stalks to every hill and three or fours acres you can imagine how many stalks there were. My older brother and I worked many days to complete the job. We used to race to see who could get their row done first. But boy power was cheap and the job had to be done before frost. We knew we had only so much time. After it was all stripped of leaves we cut and top and pile it in small piles. You could cut one or two stalks at a time then cut the heads off and drop it in piles. Then haul it to the cane mill and pile it in long piles sometimes three or four feet high. The cane mill was made of three heavy cast iron rollers set in a cast iron frame in such a way that they all touched but one could move up and down slightly as the cane passed between them and pressed the juice out. As soon as the onions were harvested and stored it was time make sorghum. First we had to strip all the leaves off the cane while still standing in the field. We did this by making sort of a wooden sword with a good handle but not very sharp otherwise it would damage the stalk. Just start at the stalk and strike down right next to the stalk and about two or three swipes and you had the leaves. But three stalks to every hill and three or fours acres you can imagine how many stalks there were. My older brother and I worked many days to complete the job. We used to race to see who could get their row done first. But boy power was cheap and the job had to be done before frost. We knew we had only so much time. After it was all stripped of leaves we cut and top and pile it in small piles. You could cut one or two stalks at a time then cut the heads off and drop it in piles. Then haul it to the cane mill and pile it in long piles sometimes three or four feet high. The cane mill was made of three heavy cast iron rollers set in a cast iron frame in such a way that they all touched but one could move up and down slightly as the cane passed between them and pressed the juice out.

The ends of the roller went through the frame and had gears on the end and one extended higher than the others and had a long heavy pole bolted to it. It extended out about ten feet so it made about a twenty foot circle. One horse was hitched to it. A light lead pole was fastened out from the mill in front of the horse and the horse was tied to it. As the horse went forward so did the lead pole. Talk about a simple life—simple machines. That was it. All you had to do was say “get up” and it started and say “whoa,” it stopped. You never had to fill it with gas and to my memory never broke down. The first cost was low—five dollars, I think—and you didn’t have to make payments at the bank. The ends of the roller went through the frame and had gears on the end and one extended higher than the others and had a long heavy pole bolted to it. It extended out about ten feet so it made about a twenty foot circle. One horse was hitched to it. A light lead pole was fastened out from the mill in front of the horse and the horse was tied to it. As the horse went forward so did the lead pole. Talk about a simple life—simple machines. That was it. All you had to do was say “get up” and it started and say “whoa,” it stopped. You never had to fill it with gas and to my memory never broke down. The first cost was low—five dollars, I think—and you didn’t have to make payments at the bank.

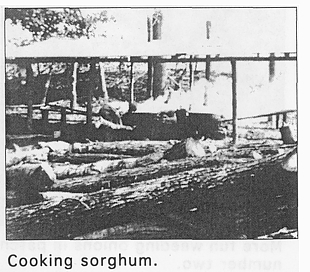

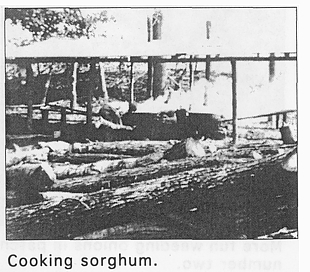

As the juice was pressed it flowed to the bottom of the press and out an opening in the side. From there it flowed through a pipe about one hundred feet into a barrel located beside the two cooking pans we used to boil it down. The pans were about two and a half feet wide and about six feet long and six or eight inches deep. They were placed on a sort of fireplace made from any rock close by and laid on top of each other to about two feet high. For mortar to hold them together we used clay mud and it served the purpose real well. Each pan held about fifty gallons of juice. A hot fire was needed to bring it to boil and then you had to skim the foam that came to the top. And after about six to eight hours as I remember it you had about five or six gallons of sorghum molasses depending on how thick you made it. I don’t remember how long it took to grind enough juice for a batch but by keeping the press running all day every day. I could have enough to make two batches a day and sometimes I could get enough ahead to make four batches a day if we started early in the morning. As the juice was pressed it flowed to the bottom of the press and out an opening in the side. From there it flowed through a pipe about one hundred feet into a barrel located beside the two cooking pans we used to boil it down. The pans were about two and a half feet wide and about six feet long and six or eight inches deep. They were placed on a sort of fireplace made from any rock close by and laid on top of each other to about two feet high. For mortar to hold them together we used clay mud and it served the purpose real well. Each pan held about fifty gallons of juice. A hot fire was needed to bring it to boil and then you had to skim the foam that came to the top. And after about six to eight hours as I remember it you had about five or six gallons of sorghum molasses depending on how thick you made it. I don’t remember how long it took to grind enough juice for a batch but by keeping the press running all day every day. I could have enough to make two batches a day and sometimes I could get enough ahead to make four batches a day if we started early in the morning.

It was a nice time of year—the weather usually nice and you had a good feeling of seeing the end result of the work you did to grow the crops. If we had two hundred gallons that meant two hundred dollars after you hauled some to town and peddled some to country people or whoever would buy it. But that was a lot of money for the times. The sorghum was usually all made by the first part of October. Then for two or three weeks us kids had a lot of free time to do what we wanted. The onions and molasses had to be hauled to town or peddled in the country. My dad usually went to town with a team and wagon. One fall we picked a wagon load of wild grapes and he hauled them to Dubuque about thirty miles. It took two days round trip. I think we got four cents a pound, and I think there was four or five hundred pounds I remember the last three or four years we were there we bought an old Model T Ford truck. We thought we really had something. I think that was I the beginning of the end of a simple way of life. It was a nice time of year—the weather usually nice and you had a good feeling of seeing the end result of the work you did to grow the crops. If we had two hundred gallons that meant two hundred dollars after you hauled some to town and peddled some to country people or whoever would buy it. But that was a lot of money for the times. The sorghum was usually all made by the first part of October. Then for two or three weeks us kids had a lot of free time to do what we wanted. The onions and molasses had to be hauled to town or peddled in the country. My dad usually went to town with a team and wagon. One fall we picked a wagon load of wild grapes and he hauled them to Dubuque about thirty miles. It took two days round trip. I think we got four cents a pound, and I think there was four or five hundred pounds I remember the last three or four years we were there we bought an old Model T Ford truck. We thought we really had something. I think that was I the beginning of the end of a simple way of life.

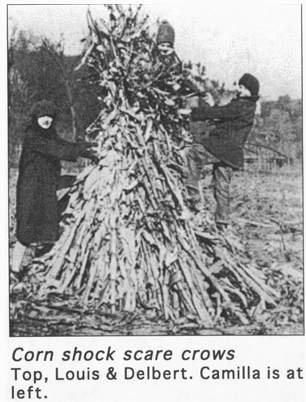

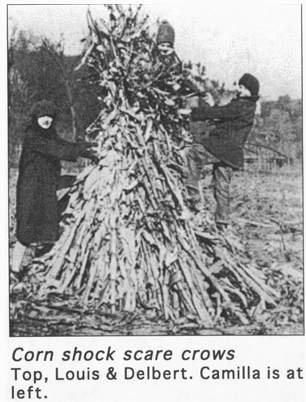

The next job was picking field corn which was not a big job for four or five of us. Of course we went to school during the week but in the morning before school and after we helped pick corn and do whatever chores had to be done. As kids I think we always looked forward to the first snow as there was lots of places to sleigh ride. We used to slide down the hills on home made sleds—scoop shovels or a piece of tin and had lots of fun. The next job was picking field corn which was not a big job for four or five of us. Of course we went to school during the week but in the morning before school and after we helped pick corn and do whatever chores had to be done. As kids I think we always looked forward to the first snow as there was lots of places to sleigh ride. We used to slide down the hills on home made sleds—scoop shovels or a piece of tin and had lots of fun.

The main job in winter was to cut wood, but that was usually done before much snow and before it got real cold. Sometimes dad would say come on kids let go to the timber and we would take some lunch—the axes and saws and walk about three-fourth of a mile. We would build a big fire from the brush and cut trees for fence posts and the tops for wood. We sometimes took the team and wagon and brought back a load of wood. Sometimes we piled the wood close to where it was cut and then hired a man with a buzz saw to cut it to stove lengths. We always kept a team of horses sharp shod in the winter because if it got icy or packed snow you could not use the horses to haul wood or anything else. Sometimes the roads drifted so deep the only way you could get out was to drive through the fields. We usually bought enough store goods like flour and sugar to last a month or more. So when a storm came we felt safe and secure until we could scoop our way out or go through the fields. The main job in winter was to cut wood, but that was usually done before much snow and before it got real cold. Sometimes dad would say come on kids let go to the timber and we would take some lunch—the axes and saws and walk about three-fourth of a mile. We would build a big fire from the brush and cut trees for fence posts and the tops for wood. We sometimes took the team and wagon and brought back a load of wood. Sometimes we piled the wood close to where it was cut and then hired a man with a buzz saw to cut it to stove lengths. We always kept a team of horses sharp shod in the winter because if it got icy or packed snow you could not use the horses to haul wood or anything else. Sometimes the roads drifted so deep the only way you could get out was to drive through the fields. We usually bought enough store goods like flour and sugar to last a month or more. So when a storm came we felt safe and secure until we could scoop our way out or go through the fields.

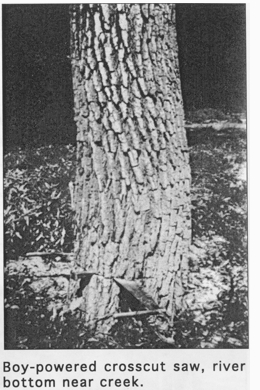

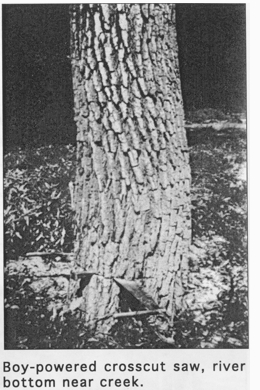

I remember one year we took the job of clearing five or six acres of heavy timber on the river bottom. Some utility company planned to build a dam at Canton and wanted all the land up river that would be flooded to be cleared of timber. I think we were paid about four hundred dollars and that was a lot of money, but a lot of work. We began in March and finished in September. With all the other work we had it was a busy summer. My older brother and I done most of the sawing with the old fashioned cross-cut saw, hand-powered. Some of the big cottonwood trees were three and up to four feet through. With a six foot saw that was hard work. They had to be cut nearly level with the ground. We had to haul away or burn everything. We had a big fire along the river bank and cut the logs in lengths that a big team of horses could pull and dragged the logs to the fire in early spring and it never went out until we were through in September. We kept piling on so many logs and it was so hot it would still be burning after a rainstorm. I was glad when it was done. Our neighbor came by one hot summer day and saw us working. He said that job was enough to make a boy leave home. But we never thought of that. We were always taught to finish what you start. I remember one year we took the job of clearing five or six acres of heavy timber on the river bottom. Some utility company planned to build a dam at Canton and wanted all the land up river that would be flooded to be cleared of timber. I think we were paid about four hundred dollars and that was a lot of money, but a lot of work. We began in March and finished in September. With all the other work we had it was a busy summer. My older brother and I done most of the sawing with the old fashioned cross-cut saw, hand-powered. Some of the big cottonwood trees were three and up to four feet through. With a six foot saw that was hard work. They had to be cut nearly level with the ground. We had to haul away or burn everything. We had a big fire along the river bank and cut the logs in lengths that a big team of horses could pull and dragged the logs to the fire in early spring and it never went out until we were through in September. We kept piling on so many logs and it was so hot it would still be burning after a rainstorm. I was glad when it was done. Our neighbor came by one hot summer day and saw us working. He said that job was enough to make a boy leave home. But we never thought of that. We were always taught to finish what you start.

When the weather begin to warm, sometime in late February, us kids would be anxious for spring to come so we could go barefooted. It seemed like forever to us for the snow to melt and the mud would be so bad you could hardly get to town with a team of horses. But spring always came and the roads got dry and we went barefooted up the hill to the grub patch and the onion patch and cane patch and a new year had begun. New but yet the same as the year before and the year after and the same until we moved away in 1930. As kids and young teenagers it was exciting to move and wonder what was ahead for us. As for me I think a small part of me remained behind. When the weather begin to warm, sometime in late February, us kids would be anxious for spring to come so we could go barefooted. It seemed like forever to us for the snow to melt and the mud would be so bad you could hardly get to town with a team of horses. But spring always came and the roads got dry and we went barefooted up the hill to the grub patch and the onion patch and cane patch and a new year had begun. New but yet the same as the year before and the year after and the same until we moved away in 1930. As kids and young teenagers it was exciting to move and wonder what was ahead for us. As for me I think a small part of me remained behind.

Today Clay Mills is a quiet and peaceful place. Nobody lives there and only rarely the sound of a human voice. But in the spring I can hear the song of the red cardinal—the cry of the whippoorwill and the hoot of the horned owl, and in summer buzz-buzz of insects and the sharp, raspy notes of the piercing cry of a hawk or turkey buzzard as they circled high in the sky. It is a forgotten place and a forgotten time for all but a few people of that time who are still living. It is a lonely place the world seems to have passed by. A way of life that many people today say they want but do not seem to be able to find. I go back once or twice a year and sit and listen to echoes of the past. I come away asking myself—has all the things that have been invented since that time made for a better life? I do not know—but I am thankful for having had that kind of a life as a boy. There were moments when I felt it was a hard life and wished I was somewhere else but not for long; for the thing I remember most clearly was the fun we had and the times when we were free to roam the hills and walked along the creek and river or through the timber wherever we chose to go. A feeling of freedom and security away from the hustle and bustle of the world. It was a place where you had time to think and enjoy each day as it came and for as long as I live I shall remember it that way. Today Clay Mills is a quiet and peaceful place. Nobody lives there and only rarely the sound of a human voice. But in the spring I can hear the song of the red cardinal—the cry of the whippoorwill and the hoot of the horned owl, and in summer buzz-buzz of insects and the sharp, raspy notes of the piercing cry of a hawk or turkey buzzard as they circled high in the sky. It is a forgotten place and a forgotten time for all but a few people of that time who are still living. It is a lonely place the world seems to have passed by. A way of life that many people today say they want but do not seem to be able to find. I go back once or twice a year and sit and listen to echoes of the past. I come away asking myself—has all the things that have been invented since that time made for a better life? I do not know—but I am thankful for having had that kind of a life as a boy. There were moments when I felt it was a hard life and wished I was somewhere else but not for long; for the thing I remember most clearly was the fun we had and the times when we were free to roam the hills and walked along the creek and river or through the timber wherever we chose to go. A feeling of freedom and security away from the hustle and bustle of the world. It was a place where you had time to think and enjoy each day as it came and for as long as I live I shall remember it that way.

—————

More of Dad's words and thoughts that inspired him to write several poems...

THOUGHTS ABOUT "A FLOWER THAT CAME FROM HEAVEN”

When we lived at Clay Mills, we took a team and wagon and went up the long hill and through the timber to where the Hovey’s lived. They were two bachelors who lived in a tar paper shack. They had several small plots of ground cleared for all kinds of garden produce and we sometimes had a small plot nearby for our own garden. They had no well, so all their water had to be carried from Clay Mills. We always took a ten gallon can of fresh water when we went up with the team of horses and wagon. One morning in early September as we left the road and turned off to go to the shack I saw some flowers that had blossomed full bloom. They were scattered and quite far apart like they might have been volunteer. But, the ground was free of weeds and they stood straight and tall. The cool fresh air and the dew drops on the flowers, sparkling in the sunlight, was so beautiful that through all the years since I have never forgotten it. But one flower stood out from all the rest in color and beauty. Most of them were poppies of various colors, but this one was more like a mum only taller on a long stem. The petals were packed close together in a cluster about three inches in diameter. They were perfectly and evenly arranged. A dark blue then a snow white—a dark blue then a snow white—and on and on to look perfectly blended blue and white with the dew drops on it sparkling in the sun made such an impression on my mind that I have often thought of it through the years since. In the fall when the air was cool on a sunny morning and I would go for a walk, my thoughts went back to that flower. So I wrote them down with the hope that someone other than me could enjoy the beauty of it or some other flower... When we lived at Clay Mills, we took a team and wagon and went up the long hill and through the timber to where the Hovey’s lived. They were two bachelors who lived in a tar paper shack. They had several small plots of ground cleared for all kinds of garden produce and we sometimes had a small plot nearby for our own garden. They had no well, so all their water had to be carried from Clay Mills. We always took a ten gallon can of fresh water when we went up with the team of horses and wagon. One morning in early September as we left the road and turned off to go to the shack I saw some flowers that had blossomed full bloom. They were scattered and quite far apart like they might have been volunteer. But, the ground was free of weeds and they stood straight and tall. The cool fresh air and the dew drops on the flowers, sparkling in the sunlight, was so beautiful that through all the years since I have never forgotten it. But one flower stood out from all the rest in color and beauty. Most of them were poppies of various colors, but this one was more like a mum only taller on a long stem. The petals were packed close together in a cluster about three inches in diameter. They were perfectly and evenly arranged. A dark blue then a snow white—a dark blue then a snow white—and on and on to look perfectly blended blue and white with the dew drops on it sparkling in the sun made such an impression on my mind that I have often thought of it through the years since. In the fall when the air was cool on a sunny morning and I would go for a walk, my thoughts went back to that flower. So I wrote them down with the hope that someone other than me could enjoy the beauty of it or some other flower...

“A FLOWER THAT CAME FROM HEAVEN”

The smell of fall was in the air.

A bright new day had just begun.

I saw a pretty flower growing with sparkling

dew drops in the sun. dew drops in the sun.

It shone with such a brilliant light.

I really could not understand,

Was this God’s way of sending a special

message down to man. message down to man.

Then I listened very closely and I think

I heard it say, I heard it say,

“God sent me here to bring his light until

He sends to me a message and tells me He sends to me a message and tells me

that it’s time to go.” that it’s time to go.”

Tho many years have since gone by.

I still can see that radiant light of blended

colors blue and white. colors blue and white.

With sparkling dew drops that shone so bright.

When God sends me a message and tells me that

it’s time to go, it’s time to go,

May I leave light even half as bright,

as that little flower did so many years ago. as that little flower did so many years ago.

THOUGHTS ABOUT "LORD PLEASE GRANT ME ONE MORE DAY"

I was walking late in the evening one day just as the sun was setting. It had been a beautiful day and sunset was the end of a perfect day. The thought came to mind that we all go through life taking the next day for granted. As we grow older we think more about there will not always be another day. But even though we have had a long life of many years we all feel we would like to have just a little more time. As I watched the sun go down at the end of a perfect day I thought about the end of life which comes to all of us sometime. And so to express the feeling of wanting a little more time the words came to mind. "O Lord please grant me one more day." In the following days more thoughts came to mind and I wrote them down. I am thankful that many "one more days" have been granted to me. I hope what I have written will not cause those who read it to feel depressed. It sure is not my feeling. I just thought it was a nice way to compare the end of life with end of a perfect day. I hope whoever reads this will feel the same way... I was walking late in the evening one day just as the sun was setting. It had been a beautiful day and sunset was the end of a perfect day. The thought came to mind that we all go through life taking the next day for granted. As we grow older we think more about there will not always be another day. But even though we have had a long life of many years we all feel we would like to have just a little more time. As I watched the sun go down at the end of a perfect day I thought about the end of life which comes to all of us sometime. And so to express the feeling of wanting a little more time the words came to mind. "O Lord please grant me one more day." In the following days more thoughts came to mind and I wrote them down. I am thankful that many "one more days" have been granted to me. I hope what I have written will not cause those who read it to feel depressed. It sure is not my feeling. I just thought it was a nice way to compare the end of life with end of a perfect day. I hope whoever reads this will feel the same way...

“LORD PLEASE GRANT ME ONE MORE DAY”

The sun is setting in the west, and soon

will drop below the shore.

There are some things I need to do,

So Lord please grant me one day more.

So many things I did not do.

I did not even keep the score.

But life has passed me by so fast,

0 Lord I need just one day more.

So many things I could have done and

should have done before. should have done before.

I thought I did my very best,

But Lord I need just one day more.

I would like to help those who lost their way.

So Lord please tell me what to say.

I will speak your words and cheer them on.

But Lord please give me one more day.

I promise Lord I will do these things

and maybe even up the score. and maybe even up the score.

I sure will do my very best.

But Lord I need just one day more.

The sun is setting in the west and soon

I will cress that Golden Shore. I will cress that Golden Shore.

Where I have failed please do forgive,

and grant me Lord just one day more. and grant me Lord just one day more.

THOUGHTS ABOUT "IF MY WISH WOULD COME TRUE”

How many times have we heard someone say I wish—I wish I could—I wish I had—I wish he or she would not and the list is endless. So I thought, how nice it would be if I could, by some divine power be granted one wish and have it come true, what would I wish. The list to select from is endless—like money, health, a new car, new house, trip around the world, or spare the life of a sick friend or family member. But suppose two or more family members were sick and you could have power to save only one, how would you choose? How many times have we heard someone say I wish—I wish I could—I wish I had—I wish he or she would not and the list is endless. So I thought, how nice it would be if I could, by some divine power be granted one wish and have it come true, what would I wish. The list to select from is endless—like money, health, a new car, new house, trip around the world, or spare the life of a sick friend or family member. But suppose two or more family members were sick and you could have power to save only one, how would you choose?

We live in a society that puts a high priority on happiness. For many of us that might be the first thing we think of in making a wish. But suppose we were told before the wish would be granted we had to be specific and say exactly what we wished. We could not just say I wish to be happy. But wise men have said no one can grasp happiness and hold to it. They cannot really define what it is. Happiness is something that we think we find but only for a short time. It somehow escapes and we seem to be not able to grasp it and hold on. So if we wished for happiness and had to be specific and say exactly what we wished, what would it be? Wise men who have lived through the past to the present have said happiness is not to be found in any one event or happening. But rather in a series of small things that take place each day throughout our life. Like a walk through the woods in the fall of year—a friendly talk with our neighbor. A trip to see a friend or family member who we have not seen for a long time. The list goes on and on. But most of the things we name would be of little or no concern to most of the people of the world. They would not make headlines or even be printed in the local paper. So in thinking what I would wish if my wish would come true, I wrote the following lines... We live in a society that puts a high priority on happiness. For many of us that might be the first thing we think of in making a wish. But suppose we were told before the wish would be granted we had to be specific and say exactly what we wished. We could not just say I wish to be happy. But wise men have said no one can grasp happiness and hold to it. They cannot really define what it is. Happiness is something that we think we find but only for a short time. It somehow escapes and we seem to be not able to grasp it and hold on. So if we wished for happiness and had to be specific and say exactly what we wished, what would it be? Wise men who have lived through the past to the present have said happiness is not to be found in any one event or happening. But rather in a series of small things that take place each day throughout our life. Like a walk through the woods in the fall of year—a friendly talk with our neighbor. A trip to see a friend or family member who we have not seen for a long time. The list goes on and on. But most of the things we name would be of little or no concern to most of the people of the world. They would not make headlines or even be printed in the local paper. So in thinking what I would wish if my wish would come true, I wrote the following lines...

"IF MY WISH WOULD COME TRUE"

If only one thing in this world I could do,

I would make a big wish and have it all come true.

But what would I wish, I am sure you would say,

Some might wish for great wealth and wish to be

happy every day. happy every day.

If I were a child I would wish for bright toys.

If I were a boy I would wish for a car.

Some folks might wish for fancy clothes and wish

to be a movie star. to be a movie star.

Now if all these wishes would really come true

and really make you happy, and really make you happy,

I would wish for them too.

But as you live through this life I am sure you will find.

You will not be really happy with things of this kind.

So what would I wish for if my wish would come true.

I would wish the whole world would be happy, then

I am sure I would be happy too. I am sure I would be happy too.

THOUGHTS ABOUT "MOODS OF THE WIND"

The first four lines of the following poem were thoughts I had many years ago, in 1935, when we lived in an old house one mile east of Bridgeport, Iowa. It was an unpainted, ramshackle and drafty old house. You could not only hear the wind outside, you could feel it on the inside. I slept in the upstairs and woke up one morning to the sound of a strong wind outside. As I lay there and listened, the thoughts expressed in the first four lines of the poem came to mind. In the many years that have passed since, I have had thoughts about the wind and added to the first four lines... The first four lines of the following poem were thoughts I had many years ago, in 1935, when we lived in an old house one mile east of Bridgeport, Iowa. It was an unpainted, ramshackle and drafty old house. You could not only hear the wind outside, you could feel it on the inside. I slept in the upstairs and woke up one morning to the sound of a strong wind outside. As I lay there and listened, the thoughts expressed in the first four lines of the poem came to mind. In the many years that have passed since, I have had thoughts about the wind and added to the first four lines...

"MOODS OF THE WIND"

O wind I wish that I were you.

So wild and free to roam.

North, South, East, or West you go.

It seems you have no home.

But how do you know which way to go?

Sometimes you seem so much in doubt.

You seem to feel so mean and angry,

as you turn and twist and twirl about.

Sometimes you seem so meek and gentle as

you softly touch the tall green grass or

quietly float in through the trees.

I barely hear you when you pass.

Sometimes at night you sound so lonely, I

think I hear you cry in pain.

That must be when your teardrops fall and

we all think they are drops of rain.

But you surely can't be always lonely as you

travel on your way.

There is sure to be some sunshine somewhere

and that will brighten up your day.

Now, why you have these many moods,

I surely do not understand.

But who am I to question why.

For I am sure you are in the Masters plan.

NARRATIVE BY PHILLIP OWEN

By my calculation, Dad was fifteen years old when the Hiley Owen family moved out of the isolated and nearly deserted village of Clay Mills. I'm sure, as they moved from the village, they retraced their path back over the same dirt road that Dad tells us about when he was a seven years old. By the time they moved, an ice jam had washed out the nearby bridge over the Maquoketa river—closing the sand ditch road leading to Onslow and the bigger world beyond. By my calculation, Dad was fifteen years old when the Hiley Owen family moved out of the isolated and nearly deserted village of Clay Mills. I'm sure, as they moved from the village, they retraced their path back over the same dirt road that Dad tells us about when he was a seven years old. By the time they moved, an ice jam had washed out the nearby bridge over the Maquoketa river—closing the sand ditch road leading to Onslow and the bigger world beyond.

At one time, Clay Mills may have had eight or nine families and lots of kids living within hollering distance of each other. An early plat map of the village shows a long forgotten post office. In the 1800's there was a small dam on the creek and a water powered grist mill. The post office was already closed before the Hiley Owen family moved into the village. Thanks to the Owen's and a few other families—the little one room school managed to stay open, delivering the three R's, for grades one through eight. When the Hiley Owen family moved from Clay Mills in 1930, they left very few people behind and took precious few possessions with them. The great depression of 1930's would soon affect the lives of many people living far beyond the tiny Jones County village of Clay Mills. At one time, Clay Mills may have had eight or nine families and lots of kids living within hollering distance of each other. An early plat map of the village shows a long forgotten post office. In the 1800's there was a small dam on the creek and a water powered grist mill. The post office was already closed before the Hiley Owen family moved into the village. Thanks to the Owen's and a few other families—the little one room school managed to stay open, delivering the three R's, for grades one through eight. When the Hiley Owen family moved from Clay Mills in 1930, they left very few people behind and took precious few possessions with them. The great depression of 1930's would soon affect the lives of many people living far beyond the tiny Jones County village of Clay Mills.

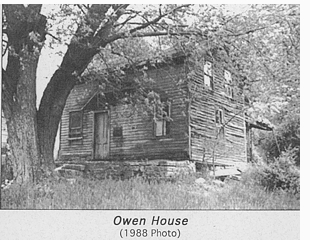

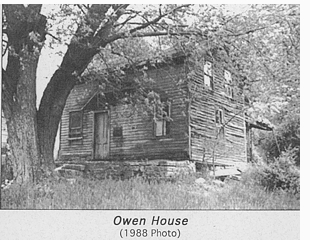

Time and nature have removed all but the last few signs marking the site of Clay Mills. Birds still fly overhead, cattle roam the hills, snakes and bugs crawl freely as ever. Gazing northwest, from the old house and looking across the creek, you can still see faint traces of the old road leading up the hollow toward Temple Hill. If you know where to look, about half-way up on the hillside, across the creek, you can find the remains of the old school house hidden under some berry bushes. Time and nature have removed all but the last few signs marking the site of Clay Mills. Birds still fly overhead, cattle roam the hills, snakes and bugs crawl freely as ever. Gazing northwest, from the old house and looking across the creek, you can still see faint traces of the old road leading up the hollow toward Temple Hill. If you know where to look, about half-way up on the hillside, across the creek, you can find the remains of the old school house hidden under some berry bushes.

Until the last few years of his life, I had only a hint of the deep and lasting memories Dad held for the place called Clay Mills. During the last years of his life, Dad became inspired to write several poems. For each of his poems, except the following poem, he wrote some words of background. I'm sure his story "Living at Clay Mills in the 1920's" gives all the background we need to understand why he wrote the following words... Until the last few years of his life, I had only a hint of the deep and lasting memories Dad held for the place called Clay Mills. During the last years of his life, Dad became inspired to write several poems. For each of his poems, except the following poem, he wrote some words of background. I'm sure his story "Living at Clay Mills in the 1920's" gives all the background we need to understand why he wrote the following words...

CLAY MILLS

I know of a place

That is called Clay Mills

It consists mostly

Of hollows, rocks and hills

A creek flow through there

A river runs nearby

And in the summertime

Turkey buzzards circle in the sky

It is an out of the way place

But very special to me

For as a young boy

That is where I used to be

I roamed those old hills

And walked by the streams

And spent a lot of time

In my boyhood dreams

Every bluff had a name

Or sometimes we'd pretend

Like Eagle Rock, Hawk Rock

Or maybe Ox Bow Bend

The old sink hole-the lime kiln

And the old house on the hill

Bring back pleasant memories

And I'm sure always will

I traveled back to that

Old place the other day

And stood and looked around

Where I used to laugh and play

The old school house is gone

And most of the other houses too

The two creek bridges are gone

And nobody travels through

Our old house still stands there

And the creek still flows by

But something else seems missing

And now I know why

There's no sound of voices

So happy and gay

No shouts of laughter

And no children play

It seems so quiet

And peaceful here today

But it seems so lonely

Since we went away

Then my thoughts turn back

To my boyhood dreams

When I roamed these hills

And walked by the streams

So I'll cherish the thoughts

Of that happier day

And I will always remember

This place that way

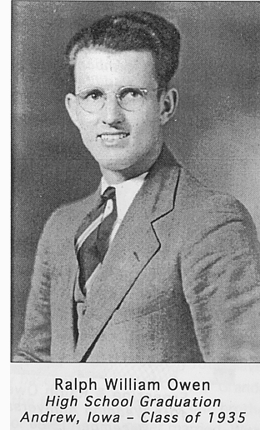

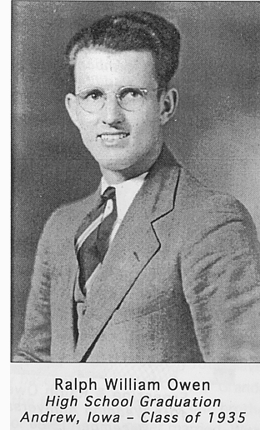

In 1930, Dad and his brothers and sisters moved out into a bigger world than they had known for the past eight years. I don't know the details, but Dad had started his high school in Iowa and then decided to go to Oklahoma. I think he went to help care for his uncle Percy. He went to high school for about a year at Ardmore Oklahoma. He came back to Iowa and finished his high school education as senior class president, in a class of sixteen students in 1935, at Andrew—graduating at the age of nearly twenty-one. In 1930, Dad and his brothers and sisters moved out into a bigger world than they had known for the past eight years. I don't know the details, but Dad had started his high school in Iowa and then decided to go to Oklahoma. I think he went to help care for his uncle Percy. He went to high school for about a year at Ardmore Oklahoma. He came back to Iowa and finished his high school education as senior class president, in a class of sixteen students in 1935, at Andrew—graduating at the age of nearly twenty-one.

Dad never said much about not reaching his goal of becoming a school teacher. He did mention that he tried to earn some money while he attended classes at the Iowa Normal Teachers College. The autumn of 1935 was in the middle of the great depression and jobs very hard to find. With little money and no jobs to be found, he came home before college classes started. He worked for a short stint on the WPA project, helping build the lock and dam at Bellevue Iowa. The cement dust gave him some problems, so he went back to working as a hired farm hand. Dad never said much about not reaching his goal of becoming a school teacher. He did mention that he tried to earn some money while he attended classes at the Iowa Normal Teachers College. The autumn of 1935 was in the middle of the great depression and jobs very hard to find. With little money and no jobs to be found, he came home before college classes started. He worked for a short stint on the WPA project, helping build the lock and dam at Bellevue Iowa. The cement dust gave him some problems, so he went back to working as a hired farm hand.

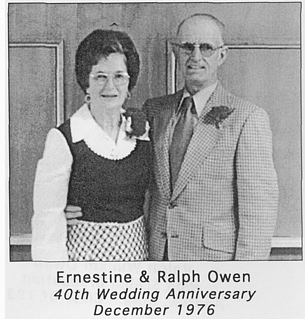

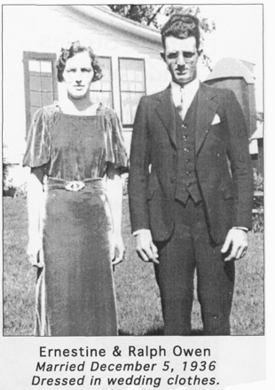

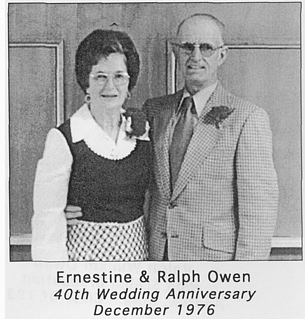

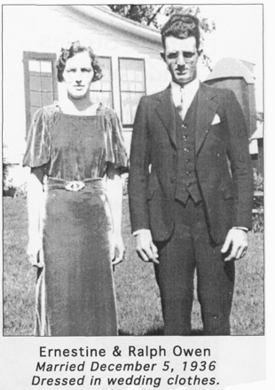

Ralph William Owen met my Mother, Ernestine Marie Miller when they lived across the road from each other, near the Stoney Point School east of Maquoketa. Mom's brother, Uncle Wilford, has shared many stories about the good times he had hunting and trapping with Owen boys while they lived across the road. Dad and Mom were married on December 5, 1936. By March, 1937, they were living upstairs, at the Gene Davis farmstead just north of Maquoketa. Dad worked as a hired farm hand and Mom worked as cook and cleaning lady. They worked and lived at the Gene Davis farm until October 1937. Then they moved in at the Art Wendel dairy farm, east of Maquoketa and again started working as hired help. In December 1939, they had saved a "little" money—and looking for a new challenge, Dad and Mom moved to a hilly farm known as the Rutenbeck place, on the Caves Road, about eight miles northwest of Maquoketa. Ralph William Owen met my Mother, Ernestine Marie Miller when they lived across the road from each other, near the Stoney Point School east of Maquoketa. Mom's brother, Uncle Wilford, has shared many stories about the good times he had hunting and trapping with Owen boys while they lived across the road. Dad and Mom were married on December 5, 1936. By March, 1937, they were living upstairs, at the Gene Davis farmstead just north of Maquoketa. Dad worked as a hired farm hand and Mom worked as cook and cleaning lady. They worked and lived at the Gene Davis farm until October 1937. Then they moved in at the Art Wendel dairy farm, east of Maquoketa and again started working as hired help. In December 1939, they had saved a "little" money—and looking for a new challenge, Dad and Mom moved to a hilly farm known as the Rutenbeck place, on the Caves Road, about eight miles northwest of Maquoketa.

World War II started—and soon all four of Dad's brothers enlisted in the military. Dad already had a family and was farming, so he stayed on the home front and listened to evening news each night to hear the latest reports. Unlike some families, all four of the Owen boys came home safely. Dad and Mom farmed on share-crop or paid cash rent for a few years before buying the 240 acre farmstead. They lived on the Cave's Farm until 1957, raising a family of four boys—who now have similar memories of growing up, free to roam the hills and have lots of fun. World War II started—and soon all four of Dad's brothers enlisted in the military. Dad already had a family and was farming, so he stayed on the home front and listened to evening news each night to hear the latest reports. Unlike some families, all four of the Owen boys came home safely. Dad and Mom farmed on share-crop or paid cash rent for a few years before buying the 240 acre farmstead. They lived on the Cave's Farm until 1957, raising a family of four boys—who now have similar memories of growing up, free to roam the hills and have lots of fun.

Dad and Mom were able to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary. For that occasion, Dad composed a special poem and had it printed on parchment paper, with gold trim border... Dad and Mom were able to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary. For that occasion, Dad composed a special poem and had it printed on parchment paper, with gold trim border...

OUR GOLDEN WEDDING DAY

December, 5, 1986

On this our Golden Wedding Day

I have some things I'd like to say.

Through all the these years of wedded life

You've been a good and faithful wife.

You've kept your promise that said "I do"

And I thank for your love so true.

You've been a good mother with love to spare

For those whom God gave you to take care.

You always were thoughtful to those you love dear

Bringing hope and happiness and lots of cheer.

You worked long hours and never complained,

You sacrificed yourself that others might gain.

You always had patience whatever the score

You lived for your family and asked little more.

For all you have done I say "Thank You",

What more can I say, God Bless you,

I love you, On this our Golden Wedding Day.

Dad moved to his eternal home and final place of rest on April, 12, 1987. Mom is still living in her own home and celebrated her 89th birthday, October 27, 2002. Dad moved to his eternal home and final place of rest on April, 12, 1987. Mom is still living in her own home and celebrated her 89th birthday, October 27, 2002.

Postscript To All Readers:

Written words can give special meaning to cherished memories for the generations yet unborn. The hope is, that you might be inspired to honor future generations by writing the eye witness account of your memories. Written words can give special meaning to cherished memories for the generations yet unborn. The hope is, that you might be inspired to honor future generations by writing the eye witness account of your memories.

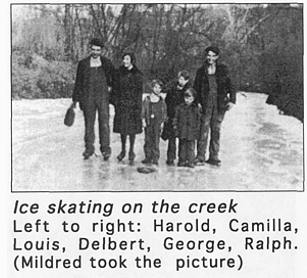

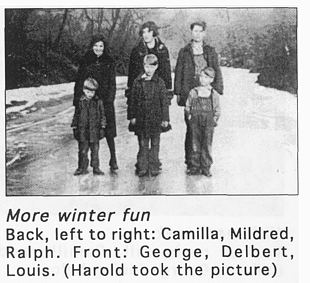

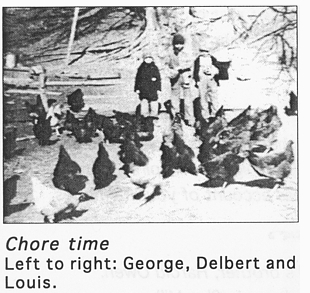

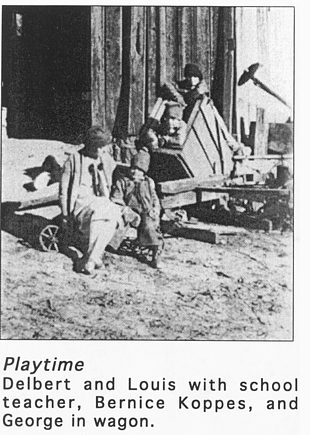

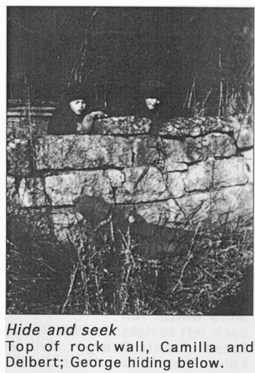

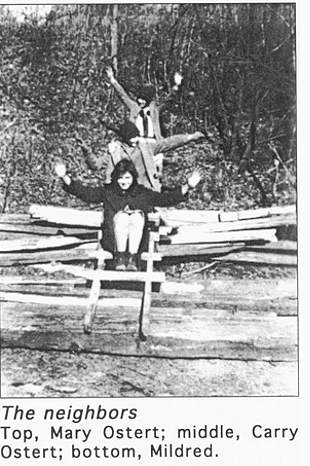

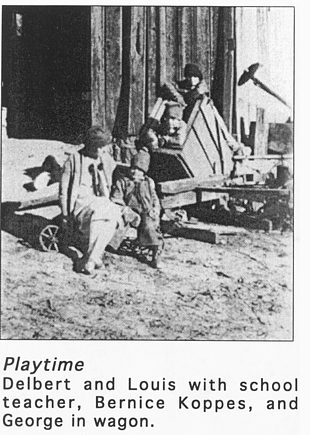

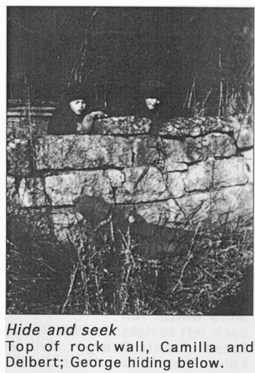

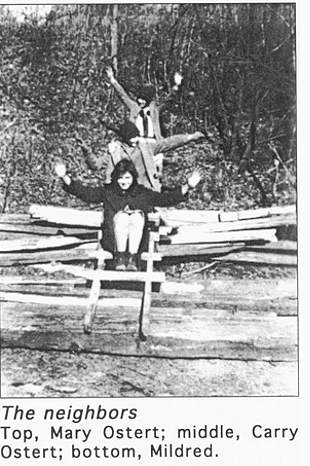

Pictures were taken by Dad's brother, Harold Owen, using a box camera, while living in Clay Mills. Pictures were taken by Dad's brother, Harold Owen, using a box camera, while living in Clay Mills.

|

|

|

I remember well the spring we moved to Clay Mills. It was late March or early April. I was seven years old. I remember very well of walking along the dirt road a half mile or more east of Clay Mills with my younger sister, driving five or six cows and wondering what it would be like when we got there. There was six of us kids (George was born later at Clay Mills) and I was third from the oldest. So, for my older brother and two sisters it was, an exciting time. As we went down the long hill to where the house and building were, we saw the creek running below the hill and all the big rocks and trees on the hillside and talked about what a nice place to be to just have fun. This was before TV, radio, telephone or even RFD (Rural Free Delivery of mail). We walked about a mile to get any mail. So, what fun we had, we made ourselves, but always found something for excitement.

I remember well the spring we moved to Clay Mills. It was late March or early April. I was seven years old. I remember very well of walking along the dirt road a half mile or more east of Clay Mills with my younger sister, driving five or six cows and wondering what it would be like when we got there. There was six of us kids (George was born later at Clay Mills) and I was third from the oldest. So, for my older brother and two sisters it was, an exciting time. As we went down the long hill to where the house and building were, we saw the creek running below the hill and all the big rocks and trees on the hillside and talked about what a nice place to be to just have fun. This was before TV, radio, telephone or even RFD (Rural Free Delivery of mail). We walked about a mile to get any mail. So, what fun we had, we made ourselves, but always found something for excitement.

Our life was unhurried and slow paced. Each day was lived like the day before—no big decision to make—like buying a new car or tractor or anything else, for we bought very little except for few basic food items like flour, sugar and other things that could not be grown. We had no bills, like heat, water, telephone, electricity or liability insurance or car insurance or health insurance. These were all things which I had never heard about. Any changes were routine—like the weather and the seasons. While work changed according to the time of the year, it was much the same year after year.

Our life was unhurried and slow paced. Each day was lived like the day before—no big decision to make—like buying a new car or tractor or anything else, for we bought very little except for few basic food items like flour, sugar and other things that could not be grown. We had no bills, like heat, water, telephone, electricity or liability insurance or car insurance or health insurance. These were all things which I had never heard about. Any changes were routine—like the weather and the seasons. While work changed according to the time of the year, it was much the same year after year.

The next big job was weeding onions. The rows were about fifteen inches apart. The seedlings as they came up were very small and grew slow so every row had to be weeded by hand. It was slow and hard, tedious work but we done it because we had to earn some cash any way we could. There was no minimum wage or no part-time jobs to be had. Day after day it was the same job. Every morning my dad would say "Come on kids lets go up to the hill to the onion patch." It was always up the hill because there was no other way, and we always went without complaining. Many years later my younger sister asked me, "How come when Dad said come on let's go up to the onion patch—we always went without complaining?" I said, "Well there was no other place or way to go anywhere else and we wanted to go somewhere, so we up the hill we went."

The next big job was weeding onions. The rows were about fifteen inches apart. The seedlings as they came up were very small and grew slow so every row had to be weeded by hand. It was slow and hard, tedious work but we done it because we had to earn some cash any way we could. There was no minimum wage or no part-time jobs to be had. Day after day it was the same job. Every morning my dad would say "Come on kids lets go up to the hill to the onion patch." It was always up the hill because there was no other way, and we always went without complaining. Many years later my younger sister asked me, "How come when Dad said come on let's go up to the onion patch—we always went without complaining?" I said, "Well there was no other place or way to go anywhere else and we wanted to go somewhere, so we up the hill we went."

About the first of September it was time to pull the onions. They were all pulled from the ground and tops removed and stored in a dry place so they would dry more before ready for sale. We usually stored them with tops on in the old house and then on rainy days we would top onions all day. For a boy my age it was monotonous work and there were days I dreamed of growing up and being rich—like being a banker or some other job where I had lots of money. But we also had lots of fun telling stories or talking about inventing a machine that would pick and top onions without ever having to touch them. I'm sure they have such a machine today but the bank may very well own it and probably be worn out before it is paid for. But I doubt if when they got done they have the same feeling of pride and satisfaction of having done a job that had to be done by hand and no other way to do it—a feeling of being independent and self-supporting and not having to worry about buying a machine and wondering if it would be paid for before it wore out.

About the first of September it was time to pull the onions. They were all pulled from the ground and tops removed and stored in a dry place so they would dry more before ready for sale. We usually stored them with tops on in the old house and then on rainy days we would top onions all day. For a boy my age it was monotonous work and there were days I dreamed of growing up and being rich—like being a banker or some other job where I had lots of money. But we also had lots of fun telling stories or talking about inventing a machine that would pick and top onions without ever having to touch them. I'm sure they have such a machine today but the bank may very well own it and probably be worn out before it is paid for. But I doubt if when they got done they have the same feeling of pride and satisfaction of having done a job that had to be done by hand and no other way to do it—a feeling of being independent and self-supporting and not having to worry about buying a machine and wondering if it would be paid for before it wore out.

As the juice was pressed it flowed to the bottom of the press and out an opening in the side. From there it flowed through a pipe about one hundred feet into a barrel located beside the two cooking pans we used to boil it down. The pans were about two and a half feet wide and about six feet long and six or eight inches deep. They were placed on a sort of fireplace made from any rock close by and laid on top of each other to about two feet high. For mortar to hold them together we used clay mud and it served the purpose real well. Each pan held about fifty gallons of juice. A hot fire was needed to bring it to boil and then you had to skim the foam that came to the top. And after about six to eight hours as I remember it you had about five or six gallons of sorghum molasses depending on how thick you made it. I don’t remember how long it took to grind enough juice for a batch but by keeping the press running all day every day. I could have enough to make two batches a day and sometimes I could get enough ahead to make four batches a day if we started early in the morning.

As the juice was pressed it flowed to the bottom of the press and out an opening in the side. From there it flowed through a pipe about one hundred feet into a barrel located beside the two cooking pans we used to boil it down. The pans were about two and a half feet wide and about six feet long and six or eight inches deep. They were placed on a sort of fireplace made from any rock close by and laid on top of each other to about two feet high. For mortar to hold them together we used clay mud and it served the purpose real well. Each pan held about fifty gallons of juice. A hot fire was needed to bring it to boil and then you had to skim the foam that came to the top. And after about six to eight hours as I remember it you had about five or six gallons of sorghum molasses depending on how thick you made it. I don’t remember how long it took to grind enough juice for a batch but by keeping the press running all day every day. I could have enough to make two batches a day and sometimes I could get enough ahead to make four batches a day if we started early in the morning.

I remember one year we took the job of clearing five or six acres of heavy timber on the river bottom. Some utility company planned to build a dam at Canton and wanted all the land up river that would be flooded to be cleared of timber. I think we were paid about four hundred dollars and that was a lot of money, but a lot of work. We began in March and finished in September. With all the other work we had it was a busy summer. My older brother and I done most of the sawing with the old fashioned cross-cut saw, hand-powered. Some of the big cottonwood trees were three and up to four feet through. With a six foot saw that was hard work. They had to be cut nearly level with the ground. We had to haul away or burn everything. We had a big fire along the river bank and cut the logs in lengths that a big team of horses could pull and dragged the logs to the fire in early spring and it never went out until we were through in September. We kept piling on so many logs and it was so hot it would still be burning after a rainstorm. I was glad when it was done. Our neighbor came by one hot summer day and saw us working. He said that job was enough to make a boy leave home. But we never thought of that. We were always taught to finish what you start.